Dream no small dreams, for they have no power to move the hearts of men. — Goethe

Dream no small dreams, for they have no power to move the hearts of men. — Goethe

To a great extent, Windridge is the result of dreams – the quests of two notable Indianapolis residents who lived their lives to the fullest. They were men who possessed the confidence, imagination, and resources to fulfill their visions.

Stoughton Fletcher once owned vast acreage in the Fall Creek Valley, which included today’s Windridge. The mansion he built was, for several decades, the largest private home in Indiana…and “Laurel Hall” quickly became the prestige destination for local society and visiting dignitaries. Robert Welch recognized an opportunity to create a style of living that was rare for its time and forever changed the area once known as Millersville. His commercial and residential developments were among the best in the city. Both men achieved great success in their professions but were later visited with great tragedy. Yet without their risks and perseverance Windridge would never have become the unique community we call our home.

|

|

| Stoughton A. Fletcher | Robert V. Welch |

It All Begins With The Land

The land we occupy was acquired from Native Americans in 1818. The Treaty of St. Mary’s, between the United States and the members of the Miami, Delaware, and Pottawatomie Indian tribes, opened much of Indiana and Ohio to development by Euro-American settlers. Originally called the Fall Creek Settlement, the area was sparsely populated by early farmers and fur traders. Eventually the number of families grew, clustered around the pure water and the assorted mills it supported.

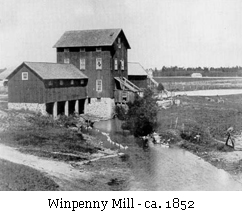

By the middle of the 1880s the town of Millersville showed up on maps, but it was never formally laid out or incorporated. However the area flourished and eventually at least four mills were needed to handle grain production from the many nearby farms. The William Winpenny mill, built in 1839, was located not far from today’s Windridge entrance. One of the largest, its upper floor also served as an early meeting place for the newly formed Millersville Masonic Lodge. The members built their own building in 1925, which still stands. Another nearby structure, now called the Flower Mill Garden Center, served as an 1800s inn for travelers.

The town grew as simple cabins and shacks gave way to over 100 homes spread over a large area centered around what is now the intersection of 56th and Emerson Way. It was a stopping point on the roads between Indianapolis and towns such as Pendleton, Waverly, and Allisonville. The old Pendleton Toll Road required payment of 3 cents per horse and rider. A post office, general store, and blacksmith provided for people’s needs. Over the years the little town prospered, but as time passed many of the homes and shops were torn down to make way for new developments. A few of the original homes from the 1880s can still be seen on Dequincy St., just west of Emerson…but the town of Millersville, and its way of life, have mostly disappeared.

homes and shops were torn down to make way for new developments. A few of the original homes from the 1880s can still be seen on Dequincy St., just west of Emerson…but the town of Millersville, and its way of life, have mostly disappeared.

The Fletcher Connection Begins

Stoughton’s ancestors first migrated to Indiana from the eastern United States in 1821. Calvin Fletcher (1798-1866) became the state’s first lawyer and was later elected to the legislature. He and his wife Sara produced nine sons and two daughters, several of whom went on to successful careers.

Calvin and 2nd wife, Keziah Fletcher

In addition to being interested in land speculation and business ventures, Calvin was a highly successful farmer. The family purchased 270 acres of prime farmland that was eventually subdivided to create today’s “Fletcher Place” neighborhood southeast of downtown Indianapolis.

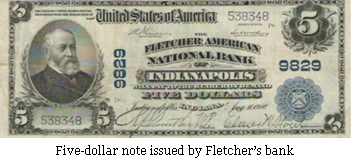

Calvin’s younger brother, Stoughton A. Fletcher, heard there was further opportunity for financial success and moved from Vermont to Indianapolis in 1831. Soon thereafter he founded Fletcher’s Bank which grew to become the largest in Indiana. Eventually it became American Fletcher National, which was merged with Bank One, and eventually became part of the Chase brand of today. It was this Stoughton Fletcher who made the young city of Indianapolis a $51,000 no-interest loan to purchase 246 acres of farmland for a much needed municipal cemetery’ now known as Crown Hill.

In the late 1800s a second generation of Fletchers presided over the bank. Then our Stoughton, who had started as a clerk, became president in 1907 when his father unexpectedly retired. The future builder of Laurel Hall was only 36 at the time, but over the next several years he grew the bank and also made substantial investments in commodities and manufacturing. By his mid-forties this third generation Fletcher was one of the wealthiest men in the state.

Development of Laurel Hall

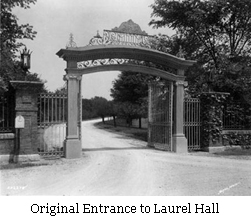

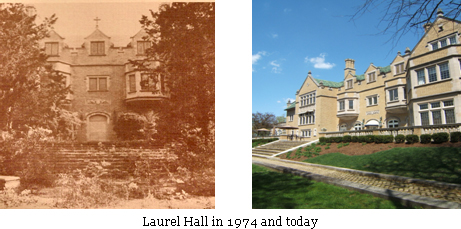

Known as The American Country Place Era, it was a time when financiers, merchants, and industrialists increased their fortunes. Families with names such as Lilly, Ayres, Allison, and Stokely searched for undeveloped areas away from the city to build their estates. It can be said that Stoughton and May Henley Fletcher surpassed them all when, in 1916, work was completed on Laurel Hall. Located on a bluff above the valley, their mansion held more than 40 rooms within its 38,000 square feet. It presided over a private domain of nearly 1,500 acres, for Stoughton had purchased a huge parcel roughly bordered by Millersville Road and what are now Arlington Avenue, 46th and 56th Streets. Visitors to the estate  entered through handsome gates located just off Millersville Road across from today’s Mallard Lake development. Curved brick walls that wrapped around to where the gates once stood can still be seen. While traveling up the long, twisting road guests were impressed by ravines and waterfalls amid rare trees imported by Alex Tuchinsky, Fletcher’s Belgian landscape architect. Water also cascaded from a Grecian temple which exists today, though now on the grounds of Cathedral High School.

entered through handsome gates located just off Millersville Road across from today’s Mallard Lake development. Curved brick walls that wrapped around to where the gates once stood can still be seen. While traveling up the long, twisting road guests were impressed by ravines and waterfalls amid rare trees imported by Alex Tuchinsky, Fletcher’s Belgian landscape architect. Water also cascaded from a Grecian temple which exists today, though now on the grounds of Cathedral High School.

A separate building, also in the English Gothic style, housed servants’ quarters and garage space, as well as enormous boilers that sent steam heat to the manor through a lengthy tunnel. They were fired by four natural gas wells dug on the property and supplied by water from Fall Creek, which had a much greater flow before Geist Reservoir was built. Completing the estate were 5 cottages, greenhouses, stables & horse trails, and even a small race track. Regrettably the tall, stone water tower and lookout, positioned for an amazing view of Fall Creek valley, was destroyed to make room for new houses east of Emerson Way.

The manor house was a triumph of architectural design by Herbert L. Bass, the noted architect of the Holcomb estate and Test Building on the Circle. At its completion Laurel Hall and its landscape had cost over $2 million, a staggering sum that would be equal to almost $37 million today. Stoughton, his wife May, and their two children Stoughton J. and Laurel Louisa settled into a house that had no equal in Indiana. According to a story in the old Indianapolis Home & Garden magazine, the structure had massive formal rooms including a drawing room, library, solarium, banquet-size dining room, and a luxurious ballroom with Gothic vaulting on the third floor.

Laurel Hall 1916

Also upstairs were over 15 bedrooms and as many bathrooms. Throughout the house more than a dozen fireplaces, each with its own distinct mantelpiece, cast their warming glow. Winding up along the three floors was a unique staircase, hand carved from native walnut trees from the estate and bathed in light from towering leaded glass windows. The latest in electric lighting and refrigeration had been installed, while an early type of central vacuum system deposited dirt to a room in the basement.

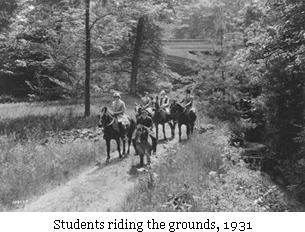

A staff of 10 was required to keep the house and grounds ready for family and guests at all times. The estate of Laurel Hall was legendary for the Fletcher’s elaborate lawn parties, balls, and equestrian events. But sadly, like so many great houses, it served its owners for only a few years.

A Princeton University graduate, Stoughton’s fortunes continued to increase as he invested in local and national opportunities. However as World War I raged on he made an untimely decision, perhaps from a combination of patriotism and a desire for greater wealth. In 1917 Fletcher responded to an urgent request for additional war machinery, chiefly large

Laurel Hall dining room

turbine engines. He bought two major industrial firms and combined them to gain their patents and manufacturing capacity – pledging his personal assets and the estate as collateral. But just when the new company had retooled and was ready for production, the war ended…much sooner than anyone had expected. The government cancelled all its contracts with Fletcher and, in 1919 he lost virtually everything. Newspapers of the time remarked that he was truly a ‘victim of the Armistice.’

Stoughton Fletcher was a ruined man, and in January of 1921 he gave up his interests in the Fletcher American Bank. Just two months later his wife, May Henley Fletcher, committed suicide in Laurel Hall by drinking hydrocyanic acid. Apparently she had been diagnosed with a terminal illness and was also suffering from depression because of their financial losses. She was just 40 years old. Her mother, Eve Henley had been staying at the mansion and found her daughter a few hours after her death. In a moment of utter despair, she drank the remaining contents of the bottle and also perished.

Laurel Hall grounds

In 1924, after exhausting every means, Fletcher declared bankruptcy listing liabilities of over $1,700,000 and assets of less than $500. Ownership of his estate was taken over by the bank he once controlled. Later he moved to California to be nearer to his son Stoughton III, who was known as “Bruz”. Reportedly he spent his senior years as an elevator operator in Los Angeles. Penniless, he moved to New York in 1952 to stay with his sister and died four years later. His ashes now rest in Crown Hill Cemetery. (As a footnote, Fletcher’s daughter Louisa died at age 24 from meningitis. The son, a well-known nightclub singer, took his own life at 34.)

The Ladywood Years

|

|

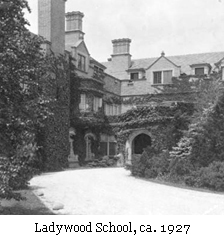

In 1925 the bank sold the buildings of the estate and several hundred acres of land to the Sisters of Providence for $600,000. Their religious order had opened the first girls’ academy in Indiana, at St. Mary-of-the-Woods near Terre Haute, and now they wished to establish a boarding school for high school students. Laurel Hall seemed to be the perfect location, and with little need for alteration the mansion provided both housing and classrooms for 60 girls. The former ballroom even made a perfect chapel for services.

Ladywood’s college preparatory program became highly regarded among educational institutions throughout the country. Many prominent families from the Midwest and both coasts sent their daughters to this prestigious school. By the 1950s enrollment had grown to over 600, requiring the construction of additional classroom buildings.

As the decades passed by several factors had a negative impact. Additional diocesan schools and other educational venues reduced the pool of students, while the costs to operate the rambling estate and its aging building continued to mount. Even a merger with St. Agnes School did not bring the income needed to continue. By 1970 Laurel Hall had outlived its usefulness and was put on the market once more.

For the next four years the estate was largely vacant and the mansion deteriorated badly. Weeds and wild honeysuckle took over the roads and riding paths, while vandals broke leaded glass windows and severely damaged the home’s interior. Concern was growing that the grounds would be subdivided and Laurel Hall destroyed.

Robert V. Welch and Windridge

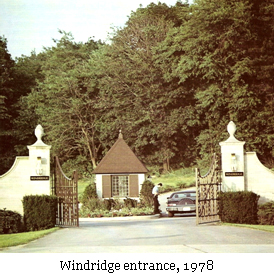

Through the early 1970s there was little building activity in the area. One change that did foster new growth was the city’s decision to straighten and extend Emerson Way, which would include a new bridge over Fall Creek. Before 1962 Emerson Avenue turned West about where our South gate is now, and curved around to an old iron bridge that led into Millersville Road. The shopping areas and offices we know today were yet to be built and Laurel Hall was surrounded by the creek and encroaching forest.

But then Robert V. Welch, a local businessman, made an historic commitment. He and his investor partners would introduce a bold plan to purchase 107 acres on both sides of Fall Creek for commercial and residential development. Welch was a highly regarded builder whose company was responsible for hundreds of homes and apartments throughout Indianapolis. Tall commercial buildings at 12th and Meridian St., as well as several along Meridian at 116th were later products of ‘R.V. Welch Investments, Inc.’

In October of 1974 a major story in The Indianapolis Star announced that the partnership would build a shopping center and restaurant on the north side of Fall Creek, and a combination of apartments and condominiums sprawling over 82 acres of woods and ravines to the south. This was remarkable at the time because, in the Midwest, the idea of condominium living was not yet popular or well understood. Such a huge undertaking was an immense gamble in those days.

One of the most prominent architectural firms in the city was chosen to design Windridge. Browning Day Pollak Associates was directed to utilize the property to its fullest but, at the same time, to respect the beauty of the land. A senior partner, Alan Day, remembers how Welch would insist that a road or entire group of condos be positioned ‘a certain way just to protect an ancient tree or maintain a special vista.’

Day also recalls that Welch insisted an old dairy barn on the property be saved, even at great cost. One of its unique features was a curved roof – supported by massive beams made for the hull of a sailing ship. Although the planners recommended it be torn down to make room for several condos, they were told to figure out a way to move the building and convert it to just two spacious units. This was a complex undertaking because the structure’s weight was as great as two good-sized homes. The finished condos, with their dramatic interiors, were featured in several magazine articles about new uses for aging commercial buildings.

Day also recalls that Welch insisted an old dairy barn on the property be saved, even at great cost. One of its unique features was a curved roof – supported by massive beams made for the hull of a sailing ship. Although the planners recommended it be torn down to make room for several condos, they were told to figure out a way to move the building and convert it to just two spacious units. This was a complex undertaking because the structure’s weight was as great as two good-sized homes. The finished condos, with their dramatic interiors, were featured in several magazine articles about new uses for aging commercial buildings.

Construction was in full swing during the late 1970s. Several model homes were created and sales begin to grow. One of the biggest draws, in addition to our secured entrance, was Welch’s new use for Laurel Hall which he renamed ‘The Manor House.’ No expense was spared in its restoration as a personal club for residents and their guests. Broken stained glass windows and damaged floors were returned to their former glory, and a large swimming pool was built overlooking Fall Creek. A private chef was hired to provide delicious meals in the huge dining room and adjoining solarium. In addition six luxurious apartments were created on the upper floors, each with one or  more fireplaces.

more fireplaces.

Dozens of Windridge homes were completed to Welch’s designs. They reflected traditional styles that used various brick facings, low-pitched roofs, and casement windows with shutters. Some can still be identified by their unique garage doors with multiple small panes of glass. Quite a few were built as single, unattached residences – which continue to be very desirable. Over several years many of the original condos were sold to people moving from large private homes in Brendonwood, Avalon Hills, Devonshire, and Meridian-Kessler.

But by the early 1980s the American economy had gone into a downturn, fueled in part by rapidly increasing interest rates. Mortgage rates, even for the most credit worthy, hit record levels… eventually reaching as high as 18%. Nearly all real estate sales slowed dramatically, with the still untested condo market hit especially hard. Some investors urged Welch to slow the construction. But as Robert Welch Jr. recalls ‘Dad kept pushing ahead with the project to help his many tradesmen and contractors who desperately  needed the work to support their families. He was that kind of a man.’ Welch and his partners tried every possible way to promote sales, even arranging for special, subsidized mortgage money. Unfortunately this too was unsuccessful and, ironically, the remaining undeveloped property was taken over by the American Fletcher National Bank.

needed the work to support their families. He was that kind of a man.’ Welch and his partners tried every possible way to promote sales, even arranging for special, subsidized mortgage money. Unfortunately this too was unsuccessful and, ironically, the remaining undeveloped property was taken over by the American Fletcher National Bank.

The Windridge Co-Owners Association was approached to purchase Laurel Hall and continue its use as a private club, but due to the extremely high operating costs the offer was declined. Fortunately, for the mansion and for Windridge, it soon became headquarters for the Hudson Institute. In 2005, after serving as a policy research organization for 20 years, this remarkable structure was purchased by the Endowment Fund of Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity. As the group’s international headquarters, Laurel Hall is now the beneficiary of the fraternity’s commitment to historic preservation.

A word about Bob Welch’s later years: Although his dream for Windridge was not completely fulfilled during his lifetime, Welch achieved notable success in many ventures. In addition to his other residential and commercial projects he was the driving force to keep Cathedral High School open. He negotiated favorable terms for the school to move from its old downtown location by purchasing much of the remaining Ladywood property and buildings. He went on to found the Fidelity Bank of Carmel, published the Indianapolis Commercial newspaper, and spearheaded the effort to build the Hoosier Dome. A 1950 graduate of Notre Dame, he was also a life-long supporter of his alma mater.

According to Bob Welch Jr., his dad’s proudest achievement was his appointment by Governor Evan Bayh as Executive Director of the newly announced White River State Park. Welch was known to ‘dream big’ and he was greatly responsible for its early planning and features including relocation of the Indianapolis Zoo. But he never lived to see the park’s completion. In 1992, at age 64, Welch and three other community leaders departed in a private plane for Columbus, Ohio. Their mission was to visit a major exhibition called ‘AmeriFlora’ to gather creative ideas for our emerging park. However minutes after take-off their plane and another small aircraft collided head-on in the cloudy skies killing all onboard. The loss to Indianapolis and its charitable organizations was profound.

Development Continues

During the following years two other builders, Gunstra and Oracle, constructed a few homes at Windridge. However the lengthy build-out period that completed our community was guided by partners Ward Horn and Ken Hansen. Their company was gaining a reputation for innovative and progressive design, so they were the clear choice to get Windridge moving forward again. As the 1980s progressed, many additional condos were constructed, several as free standing units and others in doubles, triples, or quads.

During the following years two other builders, Gunstra and Oracle, constructed a few homes at Windridge. However the lengthy build-out period that completed our community was guided by partners Ward Horn and Ken Hansen. Their company was gaining a reputation for innovative and progressive design, so they were the clear choice to get Windridge moving forward again. As the 1980s progressed, many additional condos were constructed, several as free standing units and others in doubles, triples, or quads.

Hansen & Horn models featured concepts that were just starting to be seen in Indianapolis. Their homes are characterized by ‘volume’ ceilings… some 10 ft. high or cathedral-style. Other emerging trends were large double windows with clerestory sections above, and spacious master bathrooms that provide double sinks along with a shower stall and separate tub. Probably the most unique idea, new at the time, was a ‘hearth room’ that included a kitchen opening directly to the family room with an optional fireplace. These building techniques remain highly desirable today.

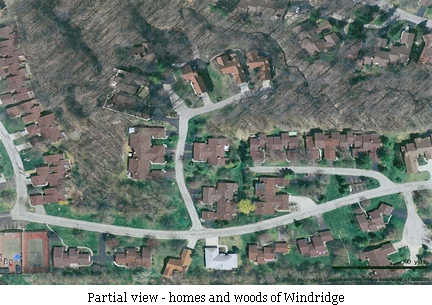

As the decade ended the idea of condominium living was becoming more familiar and increasingly popular. Potential buyers liked the idea of combining many benefits of ownership with those of renting. More people were ready to leave exterior maintenance worries to someone else and enjoy additional free time. Thus by 1995 every available space platted and approved for building at Windridge had been utilized. In all, 221 homes had been completed…yet much of the Laurel Hall’s original woods and ravines were preserved for the enjoyment of future residents.

Windridge Today

Over the decades Windridge has remained the beautiful refuge once dreamed of by Stoughton Fletcher and Robert Welch. Located near the heart of the city, our community still provides a peaceful and secure environment to share with neighbors, friends, and family. Over 300 people call it home and some of our residents have lived here 20 or more years. It’s not uncommon for people to relocate from one of our condominiums to another in Windridge when their needs and preferences  change.

change.

As we move into the future it’s also gratifying to see many new faces… people who’ve discovered that Windridge is the place they want to be. Our diverse community, great location, variety of home styles, and natural setting continue to set us apart and attract those who appreciate all that Windridge offers.

The original sales brochures from the 1970s made the following statement: ‘Windridge is not only a more satisfying place to live. It is a more satisfying way to live.’ This is still true today.